On research taste

by Albert Ying

11 February 2026

2 min read

I’ve been thinking about what people mean when they say a scientist has “good taste.” It comes up a lot in academia, usually as a compliment, but I rarely hear anyone define it clearly.

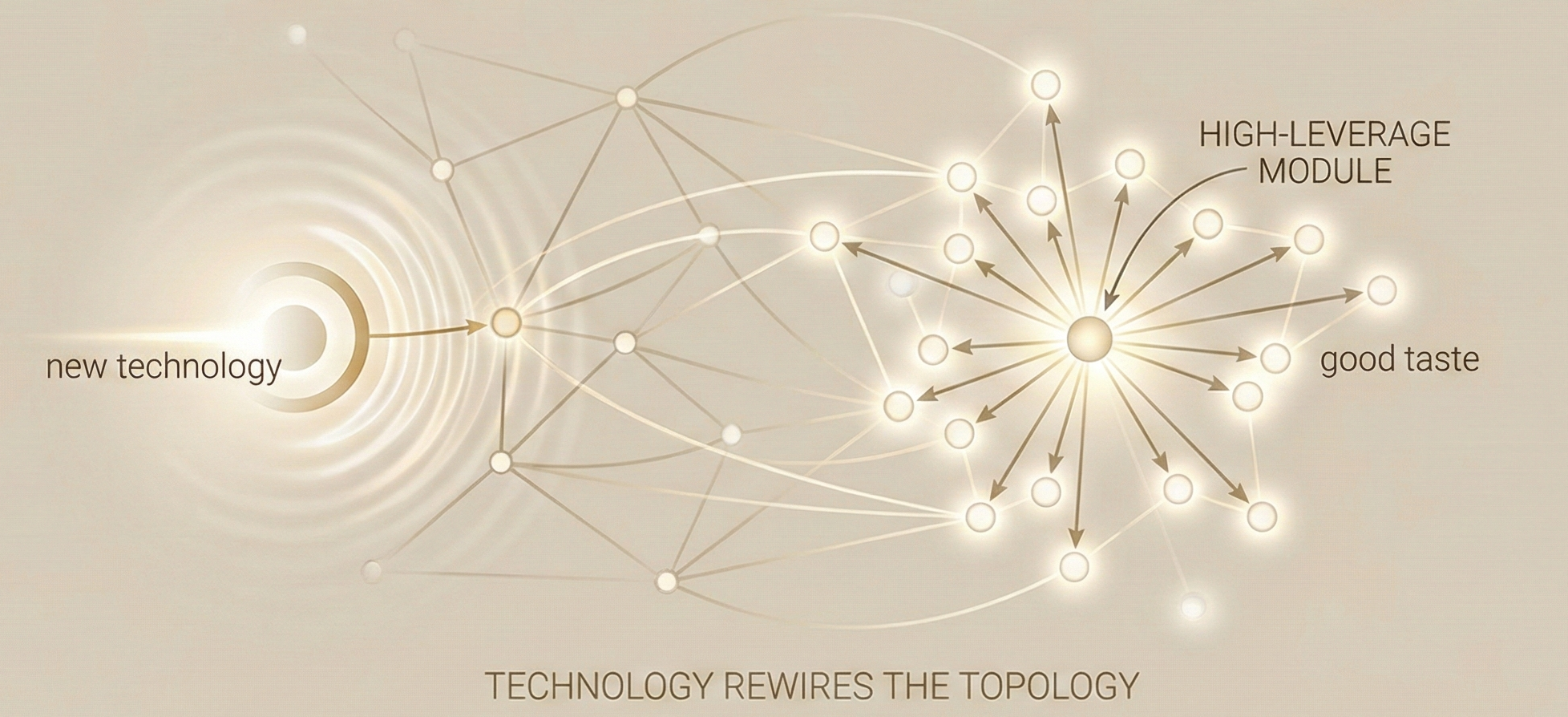

If you imagine all the hypotheses and analyses you could pursue right now as a graph, each one a node, with edges representing how one result enables or changes another, then research taste is something like the ability to find the node (or small module) that would affect the largest number of other nodes. It’s a search problem over a network.

The network is not static, though. New technology doesn’t just add nodes to the graph. It rewires connections. Things that were peripheral become central. Things that were impossible become straightforward. I think the hard part is recognizing when the topology just changed, and where the new high-leverage modules are.

Sydney Brenner had a line I keep coming back to: “Progress in science depends on new techniques, new discoveries and new ideas, probably in that order.” I think what he was getting at is that techniques rewire the graph first. Discoveries and ideas follow from whoever has the taste to read the new topology.

CRISPR might be the cleanest example of this. For decades, it was known as part of a bacterial immune system, a defense against viral DNA. A contained node sitting in the microbiology corner of the graph. Then Doudna and Charpentier showed it could work as a programmable DNA editing tool (Jinek et al., 2012). That single move created a submodule that connected to almost everything else, because DNA sits at the center of biology. Any field that touches genes suddenly had a new, precise entry point. The topology of the graph changed.

I don’t think taste is a fixed trait. The graph changes, and someone who read it well in one era can miss the next shift if they stop paying attention. The real skill is the habit of re-reading the network every time something new comes along.

But the network is too large and too complex to analyze from first principles. You can’t sit down and compute which node has the highest betweenness centrality across all of biology (maybe we can now? This sounds like a fun project with taste). Most of the time, scientists rely on an intuition about the whole network to make that judgment. And that intuition, built from years of reading the graph as it shifts, is what people mean when they say taste.